Building the Colossus LED Display

The 2014 NC Maker Faire was a huge turning point for Maniacal Labs. It was there that the idea for the AllPixel and what is now BiblioPixel got their start. It’s also where we showed off our first custom-built LED display, the 24x24 LPD8806 matrix. At nearly 24 inches square, and 1 pixel per inch, it was certainly impressive. But we left the Maker Faire with a desire to go bigger. Not just more pixels… but physically larger. Much larger. We call it “Colossus”.

This idea floated around until around December of last year, as we wrapped up the AllPixel Kickstarter. The plan: Double the resolution to 24x48 and increase the size to 4’ x 8’. But this presented some immediate problems… First, no one made LED strips in such a low density (6 pixels per foot). Second, 4’ x 8’ would not fit in my house when complete, and it would be nearly impossible to transport without a box-truck.

So, the plan was modified after choosing a spot in the home office where it would go. The new dimensions would be 1m x 2m (it was decided this would make the math easier… down with English units!). But this still left the pixel density problem. True, we could have gone with more pixels, but this was prohibitive both in cost and the required CPU power to drive the display. We then realized that the least dense we could get was the “Christmas style”, WS2812, string lights with a 12mm LED every 10-15cm along the string. They come in strings of 50 pixels, which was perfect. Even more perfect… they were cheaper than some of the LED strips. Instead of 24x48, we could do 25x50 and space the pixels 40mm apart. So, we called up our LED guy in China and ordered up a couple thousand lights… 1250 for the display and some extras for Christmas this year :)

Building Colossus

The project quickly became a total exercise in tedium… if it had to be done, it had to be done, hundreds or thousands of times. First, laying out the 40mm grid:

This was done on a sheet of 3⁄8” finished plywood, ripped down to 1m x 2m. Then, drilling 1250 0.5” holes, using a pre-made jig:

After 4 to 5 long evenings drilling holes and a couple now dull drill-bits, we were ready to frame the LED carrier:

Note: The gap at the bottom of the LED carrier is both to add a little height to get the lowest LEDs off the floor and to provide space on the back for power supplies, cables, etc. Speaking of power…

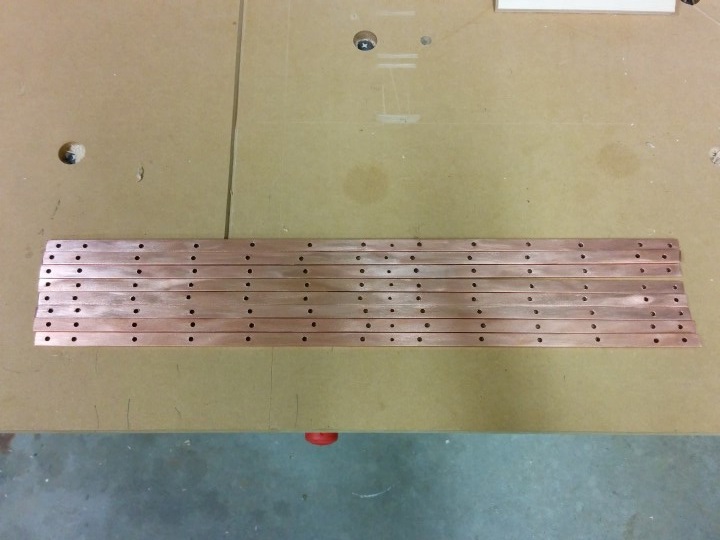

1250 LEDs require a lot of power. The calculated maximum draw is 60mA per pixel, for 1250 pixels or 75A! Since it’s 5V, that’s only 375W, but 75A will melt most wires, regardless of the voltage. 60mA per pixel is our usual rule of thumb but we admit that it’s almost impossible to get a string of LEDs to draw their calculated max. So it’s probably more like 60A max… but we always engineer for the maximum plus some extra so power is provided by two 40A @ 5V supplies. We then ran the power to four sets of custom fabricated power rails, made of 1⁄8” x 1⁄4” copper bar stock, with holes drilled for screws to easily attach the LED power wires.

These were installed at the top and bottom, using 3D printed brackets as can be seen in pictures below. But first, to install the LEDs…

Over a few more evenings, the LEDs were pressed through each of the drilled holes. For any that were too loose, they were secured on the back with a few dabs of hot glue. In the end, we decided to install the LEDs as two 25x25 matrices, top and bottom. This allowed looping back at the center of the display with each strand, making both ends connect to the same power rail at the top or bottom. This greatly simplified power since each supply could run one, symmetrical side as well as simplified driving in software them because we had two perfect squares of the same size. As you can see in the image below, electrolytic capacitors (1000uF/16V) were also attached to the power rail, one for each strand. Doing this helps keep the power flow nice and constant over each strand and reduces stress on the supply. Especially important when running at high frame-rates where one frame may be very dark and the next very bright, requiring a quick power spike.

Each of the LED string connections were made to the power rails by an M3 screw and bolt (the type used for computer hard drives). A small amount of hot glue was placed over each screw to provide a little extra mechanical durability and ensure the screws did not come out during transport.

The last two details were dividing the pixels and diffusing them. We could have let all the colors just blend together, but for this display, nice, square pixels was desired. The original plan was to use some laser-cut card stock dividers, designed by our friend Justin over at WyoLum. But this was problematic for a few reasons. First, it would require laser cutting pieces that were 1m long and access to a laser cutter large enough was expensive. We could have made smaller sections and taped them together, but we realized it was still going to require a large amount of time to complete, something we couldn’t afford and didn’t feel good about asking those who volunteered to spend the time doing. Second, the card stock would not likely hold up well to being bumped.

This led us down the road of trying to make the dividers out of 1⁄8” foam core board. We were able to acquire 30”x40” sheets that we then cut into 25mm wide strips (the height of the frame above the LED carrier, decided on by many diffuser tests). The plan, initially, was to then use a 3D printed jig to, very slowly, cut out slots in those strips (nearly 100 of them, 25 slots each). This proved to be doable but mind-numbingly slow and finicky. Fortunately, Dan had both a great idea and a saw with the right width blade (unlike mine). After making a quick jig to get the 40mm spacing down, and he was able to rip through stacks of dividers, putting perfect 1⁄8” slots in them.

We assembled those into two 25x25 grids, taped those together at the center joint, and then used 1.25” “crown” staples to tack the grid to the LED carrier board.

Last, came the diffuser. The original plan was to use a large sheet of semi-transparent white or black acrylic. This proved to be… very expensive. Since it wasn’t clear, it was a bit of a specialty item that it seemed we could only order from a few places. But none would ship a 1m x 2m sheet, and we didn’t want to break it up and have a seam. This led to a much cheaper and more creative solution; a white sheet. Two white sheets actually. We wanted to have it wrap fully around the frame so there was nothing seen holding it all on, but after some testing we found that it required two sheets to give the desired effect of seeing just a square of light and not a round point (higher thread count may have worked too). So we used a twin size sheet for the first layer and stapled it on around the sides. We then used a king size sheet over that, fully wrapping to the back, and stapled on the back edge of the frame. Pro-Tip… buy a power stapler. Yet another thing we did thousands of times. This had to be done very methodically, ensuring that both sheets were stretched taught and had no creases or bunches in them. The excess from the king sheet was simply cut off and the edges stapled in place on the back.

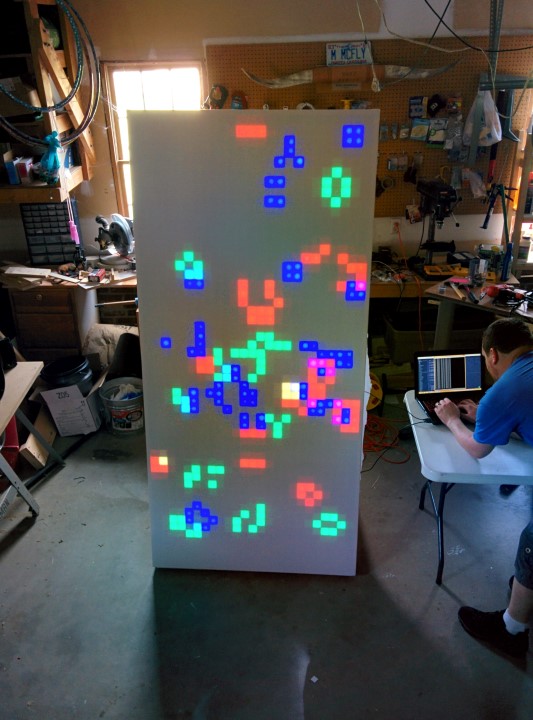

When complete, the effect looked great!

Driving Colossus

From what we’ve seen, most people use the AllPixel to drive a handful of LEDs, probably less than 200. And this is great, we’ve seen some awesome projects. But part of our drive behind Colossus was to show off what the AllPixel and BiblioPixel could do. Though the AllPixel supports 700 total pixels and not 1250, this was not a problem, because BiblioPixel was designed to support multiple displays acting as one. That’s why, as mentioned above, the display is actually made up of two 25x25 displays. Using the multiple driver support in BiblioPixel, we were able to use two AllPixels, each driving 625 LEDs, together to drive the display.

This ended up being a very necessary tactic, since there was a downside to using the much cheaper WS2811/WS2812 LEDs… they are slow. The 24x24 display made for Maker Faire uses the LPD8806 which can be clocked at up to 30Mhz, meaning super fast refresh rates. The WS2812, however, is limited to a pokey 800Khz signal over one wire which is a pain to drive; one of the reasons we created the AllPixel! This, however, means that by just doing the math on the signal rate of the LEDs and data speed of the USB serial connection to the AllPixel, the best we could possibly hope for was to update all 1250 pixels in a little under 50ms, if connected as one long run. That would mean an absolute max of 20 fps… not acceptable. Using the LPD8806 would have been great, but that’s just to expensive. We had to stick with the WS2811/WS2812.

This is where the dual drivers come in. We can update 625 pixels in about 24ms, bringing us closer to the 40 fps range, but we still had to do this twice. Fortunately, BiblioPixel has the ability to thread the driver update, pushing the pixel data out to each AllPixel at the same time. Not only that, but it means we can be generating frame data while the last frame is output. So as long as the frame was generated in less than 24ms, we could achieve a steady 40 fps. However, the display is typically limited to 30fps on each of the animations, to allow for a little wiggle room.

In the end, this worked great and we get buttery smooth animations that would never hint at it really being two separate displays working in unison. And this is all something you can do, right now, with the AllPixel (or a couple) and BiblioPixel. But stay tuned, because what we did use for the recent SparkCon is actually the development version of the new, improved, soon-to-be-released BiblioPixel v2.0… and a BiblioPixel UI! Yup, soon, you’ll be able to push pixels without touching one line of Python code… unless you want to :) But more on the software details in a near future post. The new code is almost done cooking and ready for the world :)

What We Would Change

At SparkCon, this past weekend, Colossus performed beautifully. The only real issue we saw was because I, like the programmer I am, decided it would be a good idea to add a new feature to BiblioPixel the evening between day one and day two of SparkCon… and there were a few bugs :P But the hardware was rock solid, even after being lugged to downtown Raleigh in the back of a pickup truck. But that’s not to say there’s some things we would not do differently next time or that didn’t go as originally planned.

Sour Pi

The original plan was to control both AllPixel drivers from a single Raspbery Pi 2. This could work, in theory, under certain circumstances. But as we found a week before SparkCon (yes, it should’ve been tested earlier) the Pi 2 didn’t really have the grunt. A lot of testing was done to narrow down why and it actually came down to the USB Serial output. As mentioned above, we should be able to output the data in ~24ms, but the Pi averaged 36ms per update. Yes, the frame generation was slower on the Pi than on the laptop we used to run the display at SparkCon, but it was still faster than the ideal 24ms update time so it should not have mattered. It seems that on the ARM Debian branch that the USB Serial output can become CPU bound (this doesn’t happen in Ubuntu on a regular computer). But, in the end, we are not 100% sure what the issue was. We’ve gotten much faster speeds on the Pi 2 before but this was with LPD8806 LEDs, which update much, much quicker than WS2812…

Sub-Luminal Speeds

The WS2812 LEDs were chosen because they could be had in the string form factor and they were the cheapest of the bunch. The APA102 is a close second in terms of price and are much faster, but only come in strip form at the moment and therefore had the same pixel density issues noted previously. However, building a display with more pixels than Colossus would definitely benefit from the extra cost and extra speed of a quicker LED chipset. Even the WS2801 with their 1MHz clock speed would provide at least a 25% performance boost. We can certainly scale up to using more AllPixels in order to drive everything in parallel and get a speed boost, but there’s only so much to be done. We could have likely used a Pi 2 if it were not for the LED speed and that would have be much preferred over using a big, power hungry, computer. Especially since this will be permanently installed in my home office in the coming weeks… once I find a more permanent control solution.

Durability

While the semi-transparent acrylic diffuser plan was shot down due to cost, it’s major benefit would have been greater durability than the current, cloth diffuser. A major concern for final, permanent, installation was keeping it clean and undamaged… something likely impossible in a house with two cats. One SparkCon attendee, however, gave a great suggestion of getting a sheet of thin, clear acrylic and affixing it on top of the cloth diffuser. This will keep the cloth scratch free and allow for easy cleaning over time. So, that will certainly be happening before it becomes a permanent fixture.

More to Come

Stay tuned because there will certainly be more to come. Colossus will absolutely be playing a big role in the future development of the AllPixel and BiblioPixel, for which exciting new things are coming soon!

Happy Making!